We like to call ourselves data scientists these days, so let's have a look at one of the things that makes science science: peer review. For knowledge to be counted as scientific knowledge, it has to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. All submissions to a journal have to be reviewed by a panel of subject-matter experts before they can be published. These experts subject the submitters' findings to rigorous critique.

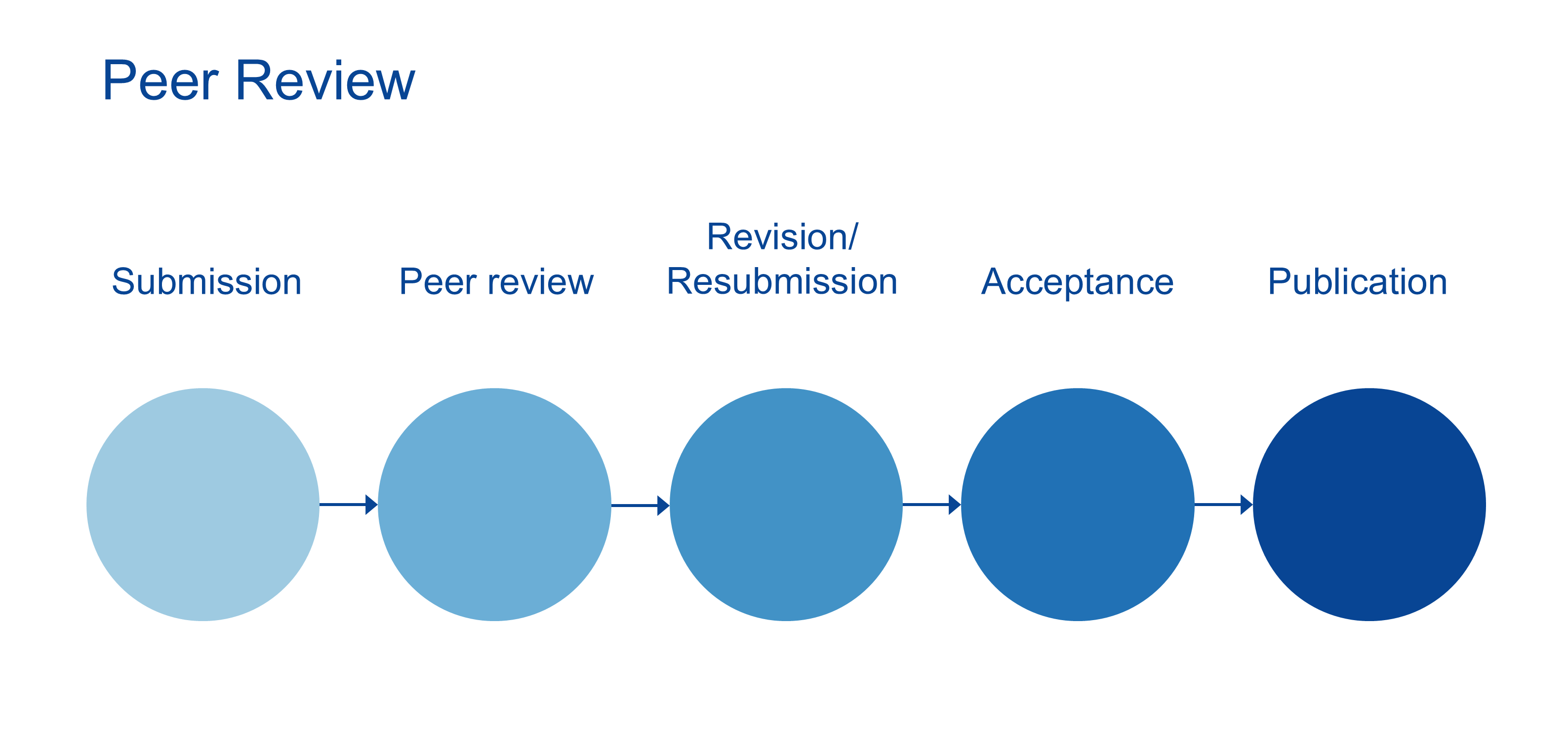

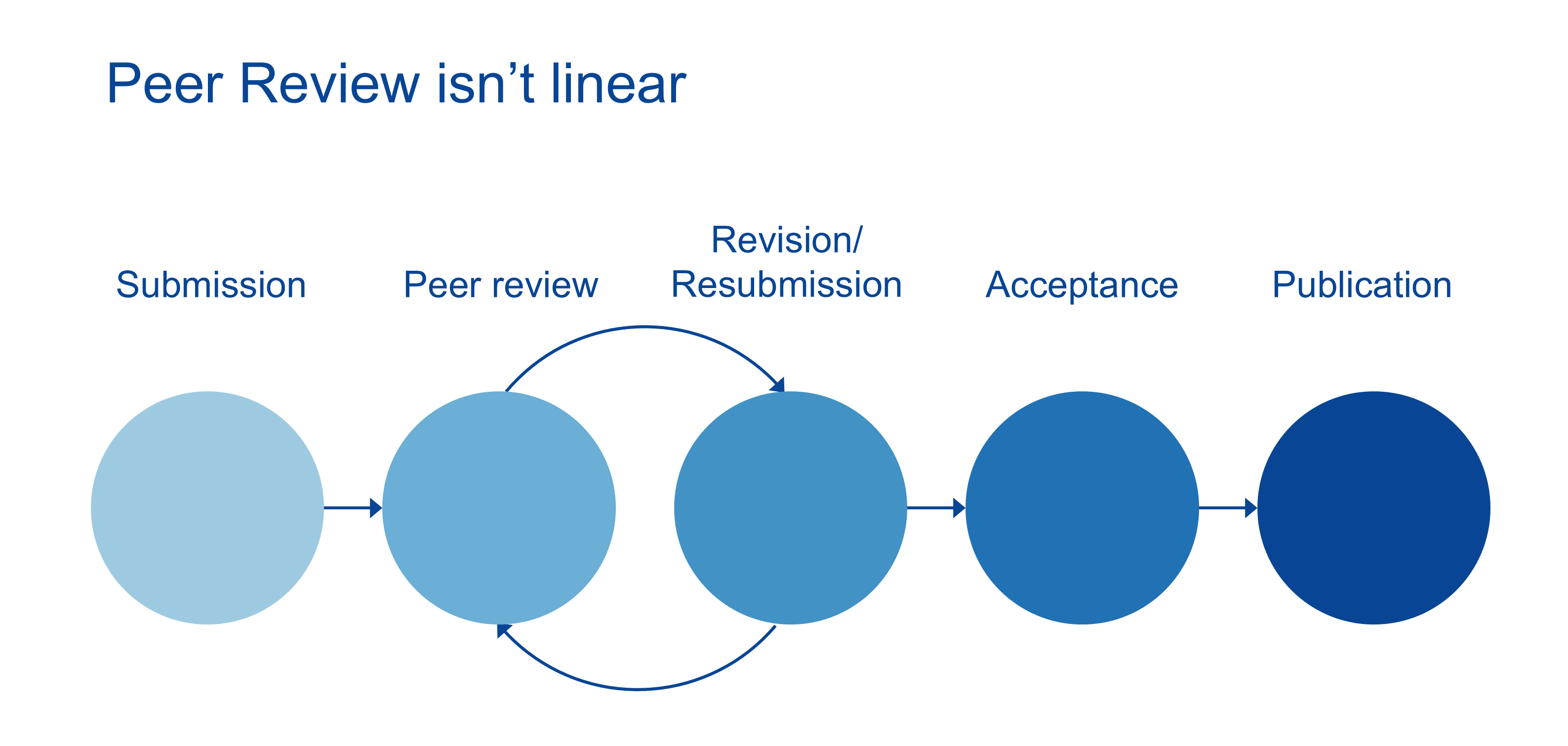

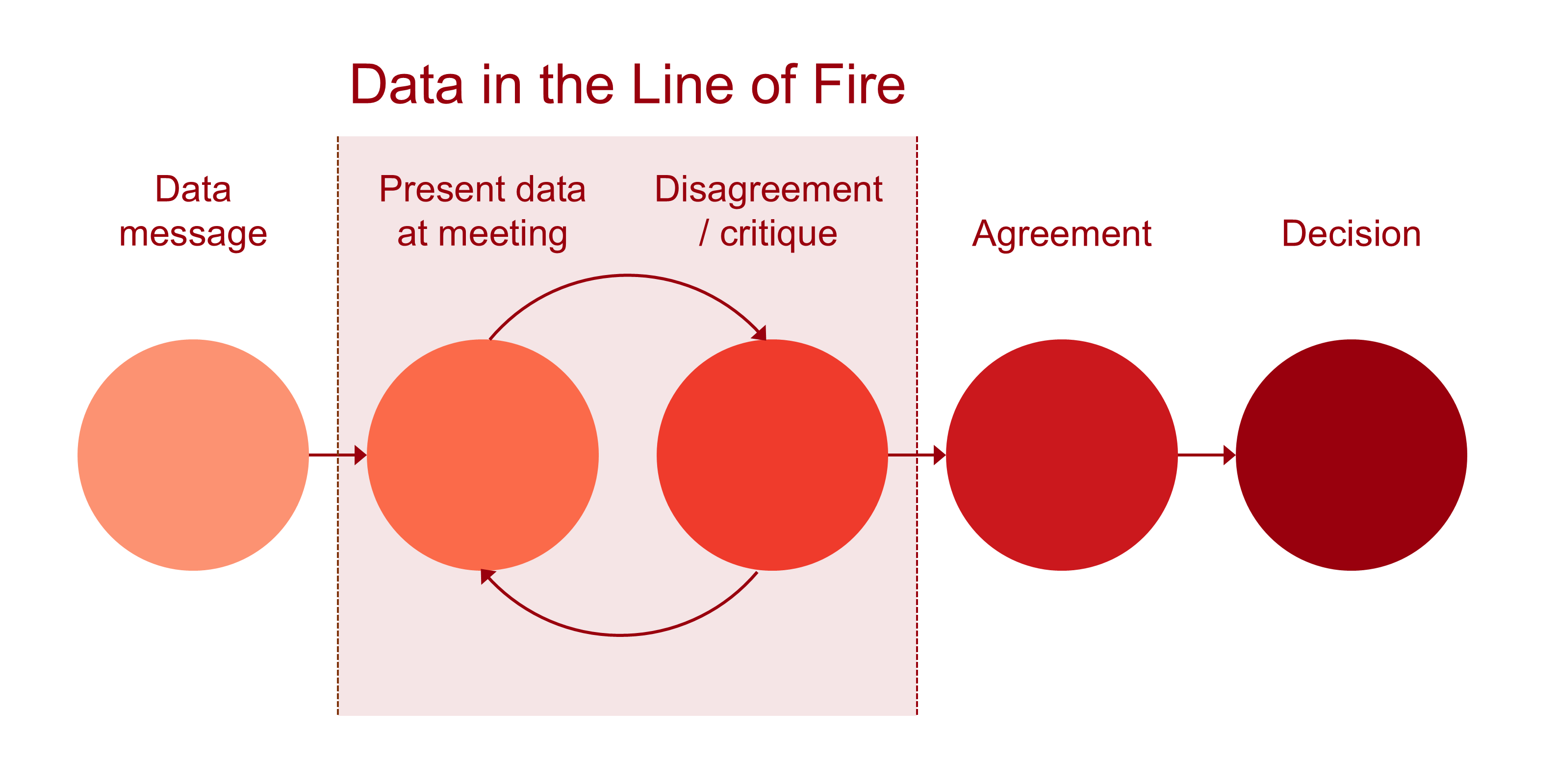

Yes, this diagram is over-simplistic. But it does allow us to focus on one particular aspect of the process: the second and third steps. That transition from peer review to revision and re-submission isn't linear; there can be to-and-fro. Although an important function of peer review is to filter and then reject submissions, it also serves as constructive feedback. So we can now re-visualize the diagram. emphasizing the to-and-fro between the second and third steps:

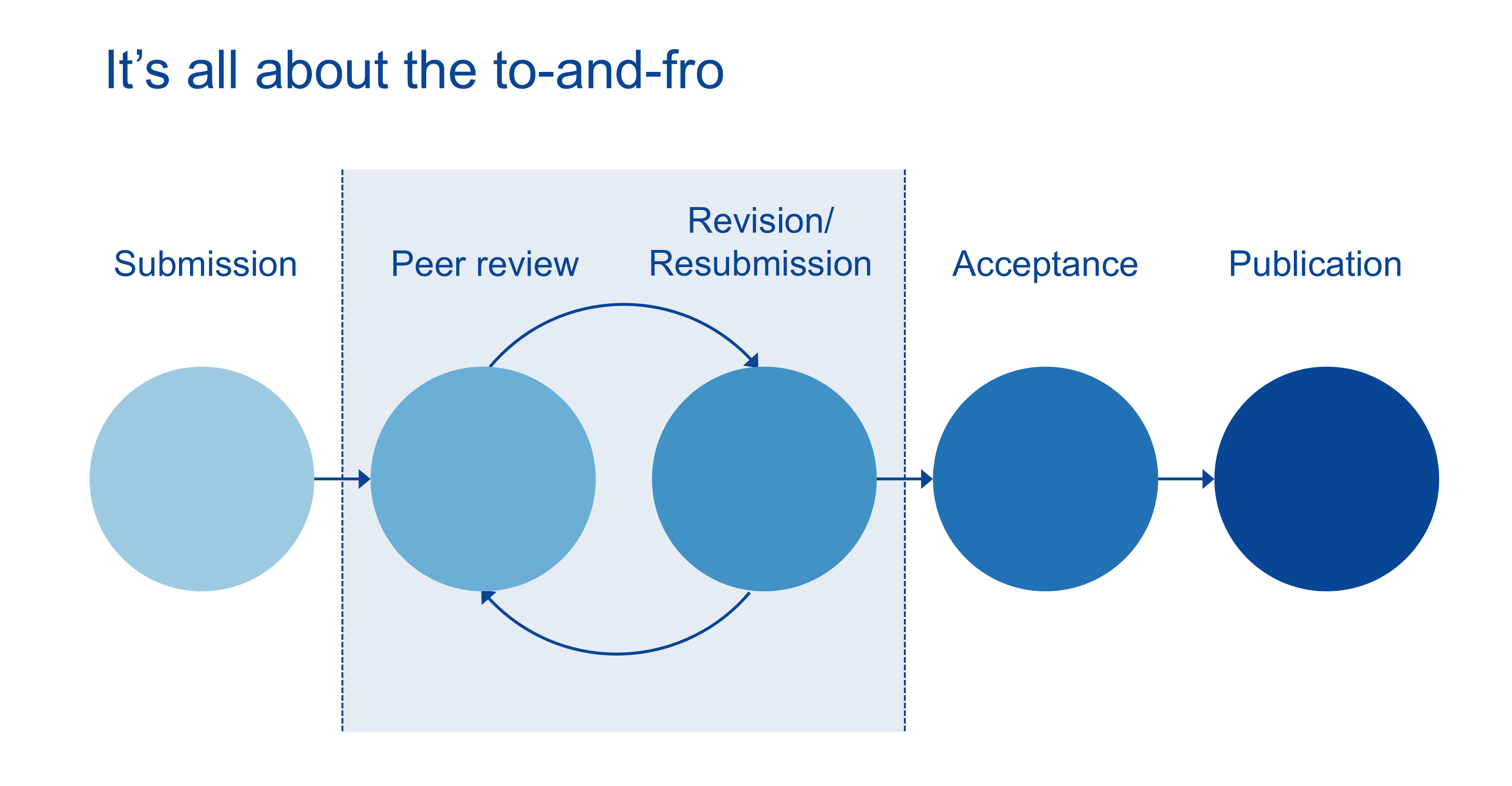

It's this to-and-fro that is at the heart of the point I want to make. Science has adopted as one of its key tenets this idea that a proposal or submission—probably pretty good to start with, and presented in a well-argued manner—has to be tested rigorously by a panel of experts, that the results of that critique are fed back to the author(s) who can then refine and re-model their work and resubmit it for publication. This is a big part of how scientific knowledge advances: the rigorous critique followed by the re-write. So the absolute key part of the process is steps two and three:

Yes, I know. Business isn't science. But if data analysts aspire to a decent level of rigour and relevance with our management information, then the way we can replicate peer review is by taking our data findings to a meeting, presenting those findings as well as we possibly can, with as much conviction as we can, and then seeing if our findings can withstand the critique of our peers (in this case, managers and clinicians).

There is an important difference from the scientific peer review process. When a paper is submitted to a peer-reviewed journal, the peers will be members of the same profession as the author(s) submitting the paper. In an NHS meeting, the peers will be multi-disciplinary. We're not asking other data analysts to review our findings; we're asking managers and clinicians to review our findings to see if they make sense to them.

If we approach meetings with this diagram as our mental model, we will think differently about meetings. Instead of fearing critique, we will be inviting critique. Yes, we will present the data like we mean it, but we will also present it with humility, because we realise that—despite our best efforts—we won't have got everything right. The meeting is where we get the opportunity to find out from our peers what we need to change to make it better.

Data in the Line of Fire can be booked as an on-site face-to-face course for £1,250+VAT, and up to eight participants can be accommodated in each workshop session. Email info@kurtosis.co.uk to start making arrangements. Open course places cost £350+VAT.